Preventing Electrochemical Contamination at the Rework Station

The choice of flux plays a significant role.

by Timothy O’Neill

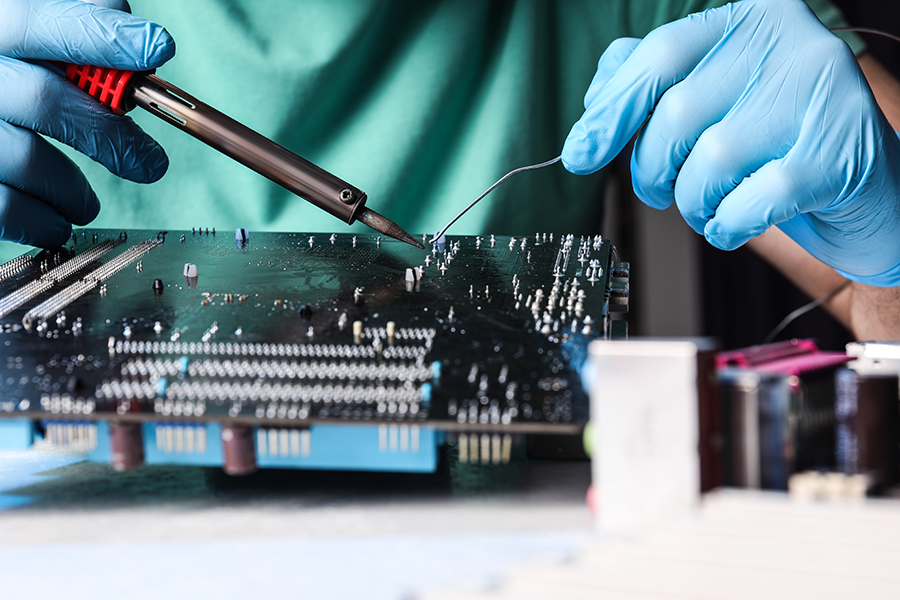

Although the rework bench plays a critical role in electronics manufacturing, engineers often overlook its cleanliness due to its lack of flashy machinery and perceived simplicity. Skilled hand solder operators proficiently completing their tasks can lull supervisors into a false sense of security, particularly since electrochemical contamination issues don’t manifest in this environment.

But in fact, as many as eight out of 10 contamination-related issues can be traced back to the rework bench. Here, we look at how these contaminations occur as well as how to prevent them by examining common products and tools in the rework bench environment.

Solder wire and flux core. Solder wire is probably the most common material found on the rework bench. It consists of a solid alloy with a flux core, typically composed of a high percentage of resin/rosin. When the tip of the soldering iron contacts the wire solder, the flux liquefies and spreads out over the workpiece. This process is facilitated by the lower melting temperature of the flux compared to the solder alloy.

One of the key advantages of solder wire with a flux core is the low risk of unactivated flux transfer – which makes it an unlikely culprit for contamination. As the flux core needs to be heated to evacuate the wire core, it becomes difficult for unactivated flux to be transferred to the workpiece. The combination of the soldering process and the materials used minimizes the chances of introducing unwanted flux residue.

Pitfalls of liquid flux. Liquid flux offers several advantages in soldering, including improved wetting and the creation of a thermal bridge between the soldering iron tip and the area to be soldered. These attributes enhance soldering performance and speed, making liquid flux a desirable option for many operators at the rework bench.

Many no-clean liquid fluxes require sufficient exposure to heat in order to render them inert, however. While this is usually ensured in full wave solder applications, rework or point-to-point selective soldering often relies on localized heat sources that may be insufficient to decompose the flux activators completely.

Another issue with liquid flux is its tendency to spread beyond the intended area during the soldering process. This spreading can cause the flux to reach and shield components from heat exposure, preventing proper soldering and potentially leading to reliability issues.

In some cases, the liquid flux used in benchtop squeeze bottles is procured from the same source as the flux used in wave-soldering operations. This is not advised. It is important to use application-specific formulas designed for rework that do not require heat for a “no-clean” classification. Alternatively, relying solely on the flux core found in wire solder can be a safer option.

Flux residue aesthetics. Even if the wire and flux materials used are safe and compatible, they may still leave enough flux residue behind after soldering to present aesthetic concerns. This residue often influences the perceived quality of the printed circuit board (PCB). Although it has no real effect on actual quality, it’s worth minimizing in order to avoid complaints.

Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) is commonly used to clean flux residue. Exposing flux residues to IPA, however, may alter their electrochemical properties. This chemical interaction may result in the creation of an undefined third product with unpredictable characteristics. The cleaning tools themselves, such as swabs, wipes and brushes, can also introduce cross-contamination.

Studies have shown that partially cleaned no-clean fluxes have lower resistivity values compared to unaltered fluxes. But if removing flux residue is important, consult the flux manufacturer for recommended cleaning chemistry tailored to the specific task of flux removal. While specialized solvents engineered for flux removal may have a higher upfront cost, they offer a more effective and safer alternative to the marginally effective IPA.

Selecting the right tools and products and using them correctly is paramount in preventing electrochemical contamination at the rework bench. Understanding the differences in materials and processes, avoiding inappropriate flux usage, and adopting appropriate cleaning practices, can ensure the reliability and quality of work at the rework bench.

Timothy O’Neill is director of product management at AIM Solder (aimsolder.com); toneill@aimsolder.com.